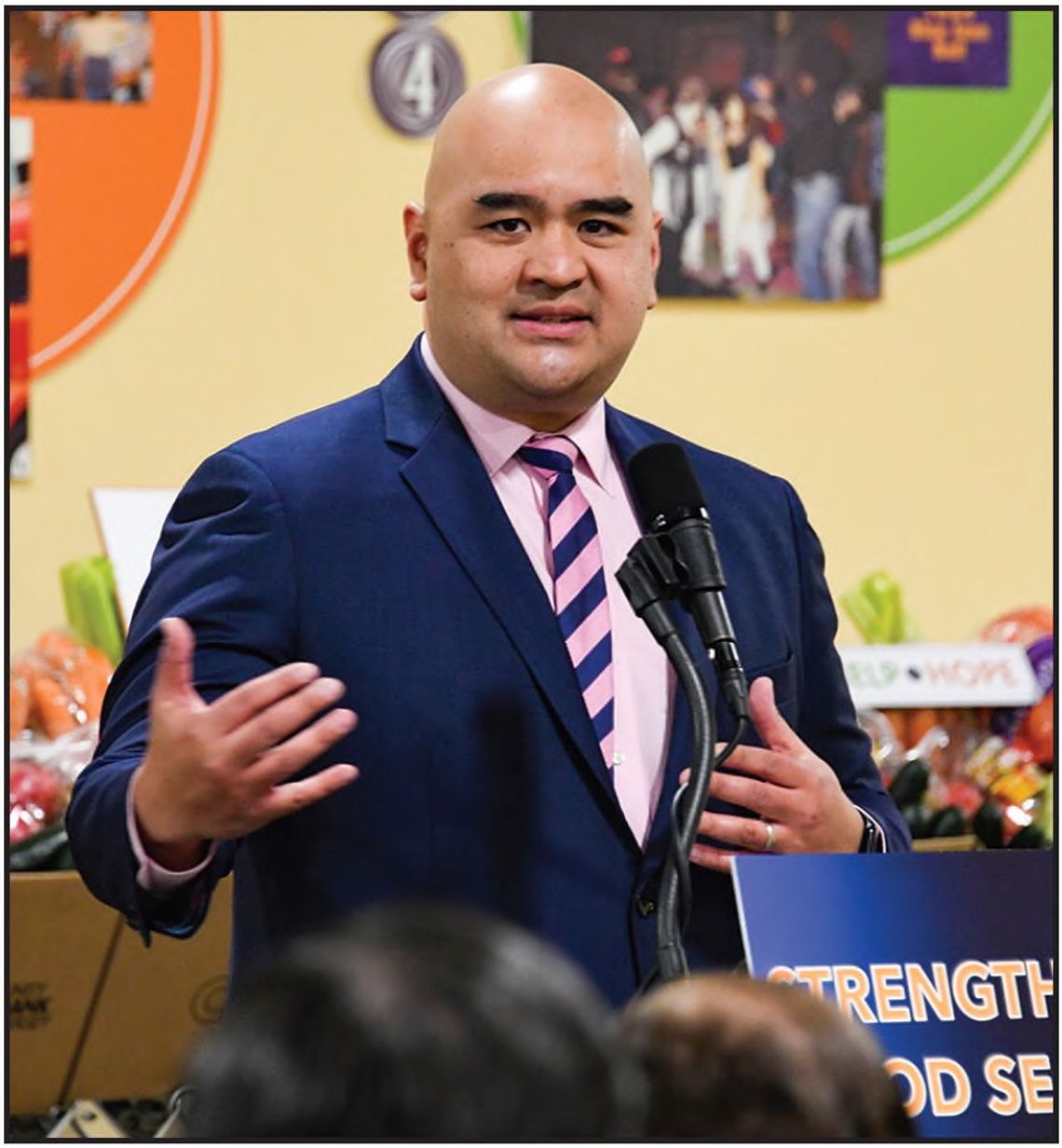

“Ending hunger has nothing to do with giving people food and everything to do with advocating for food security,” said Mark Dinglasan, when hewas appointed director of theNew Jersey Office of the Food Security Advocate in September of 2022.

The 1999 Livingston High School graduate is leading an office charged with coordinating anti-hunger efforts across the state. He says he will focus on three pockets: to help inform policy; work with philanthropy; and organize local organizations.

The legislation establishing the Food Security Office - the first of its kind in the nation - was unanimously passed by the State Legislature and signed by Governor Murphy in 2021.

Dinglasan is prepared for the task, having led CUMAC (Center of United Methodist Aid to the C ommunity), a nonprofit that fights hunger and its causes in Passaic County, for more than five years. His work there, he said, “existed at the intersection ofpreventing adversity in childhood, preventing adverse childhood experiences, and building equitable food access systems.”

Before that he advocated for juveniles in the criminal justice system as executive director of CASA of Cook County, Chicago.

Dinglasan had been away from New Jersey for 17 years, but moved back in 2016 with his wife, Michelle, when his mother was diagnosed with with breast cancer.

He decided to work in food access because of something a judge in Chicago said: “How do we empower families enough so that kids are not getting pulled out of the home?”

His holistic work at CUMAC which included the additional challenges of the pandemic, was noticed by first lady Tammy Murphy, who visited twice and then brought the governor. “Theymentioned to me how they were big fans of the team and the work that we were doing. And that garnered the attention of several state departments.” Dinglasan’s desk sits in the Department of Agriculture, but his position is in the executive branch of government.

There are other food security advocates, Dinglasan explains, but they usually report to a mayor or a county official. “I report to the Senior Policy Advisor, and I serve at the pleasure of the governor, so that makes this office unique.”

He is building up a small, “agile” team of three. His office has a budget o f $ l million.

Food Security, Not Insecurity The bill to establish the office was signed on September 20, 2021, and the name was changed from the Office of Food Insecurity to Office of Food Security in January, 2022.

“People like to joke that ‘Mark made us change the name,’ Dinglasan says. “I don’t know if I had that strong a hand in it, but when I was interviewing for this position, I told the folks that words really matter.

“I feel that, more often than not, we focus too much on combatting food insecurity rather than creating food security... Iwouldpreferwesay food security, rather than food insecurity, as much as possible.”

Ask Families What They Need More than one million people in New Jersey are estimated to be food insecure, and more than one-third of them are children.

A study by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation reports that one in 12 people in New Jersey are food insecure, meaning that they have to decide between procuring food or paying an essential bill or car payment, Dinglasan adds.

To address this problem, he feels, “It’s got to be about more than a focus on food... We have to take a more holistic, upstream, multi-sector approach.

“It’s very important that we’re still handing out healthy food on the frontlines, so food pantries and food banks have a role to play. But we have to start looking more at how we are creating economic, physical and social access to safe, sufficient and nutritious food. And how we are building self-efficacy, and agency, and community so that moms, dads, families have the power to create healthier communities, healthier households for themselves.

“I think you have to start at the community level,” he says. “Instead of observing poverty and hunger in a particular community like Paterson or Irvington and making sure a lot of food gets there, let’s flip that formula on its head, and first ask families, moms and dads, what do you need, and how can we help? Let’s make them part of the development of the solution for their community. And then let’s start building out solutions.”

Doing this work, he says, “I’ve met some of the most powerful and beautiful moms and dads. They want to be independent. Nobody wanted to come to the organization that I was running – they wanted to be able to cook breakfast for their kids on their own.

“But there was such a multifaceted struggle that they were going through. So asking them for their advice on how can I help them is the most effective way to help.”

In fact, he spoke to the West Essex Tribune from his car after talking to a health coalition in Jersey City about what families are going through. He has been up in Sussex, down in Asbury Park, and was headed to Camden the following week.

“This is an ‘all over the place’ issue,” Dinglasan said. “Frontline organizations, like the one I was running, are now seeing more people every month than they were at the height of the pandemic. Even though we aren’t seeing long lines and people in cars, the struggle is still here.”

One director told him that he sees a client, almost every week, who says that he was one of the food bank’s donors the previous year.

Growing Up in Livingston

Dinglasan’s devotion to community service began during his years in Livingston.

He moved to town with his parents, brother and sister in 1992, and lived on Hillside Terrace and then on Hobart Gap Road, where his mom still lives. His dad passed on November 2.

“We were activists at St. Philomena Church,” said Dinglasan. The three siblings did a lot of volunteer activities, and the family went on mission trips together.

“I firmly believe that’s kind of my foundational knowledge and beliefs for how I do my work,” says Dinglasan.

He played football at LHS for three years, and then took on the role of Ambrose Kemper in Hello Dolly his senior year.

After graduating, he earned a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from Monmouth University and, later, a master’s degree from DePaul College of Business.

Today, Dinglasan sings and dances and throws a ball with his 21-monthold daughter, Lily Grace.

Ministry

Halfway through his first semester of law school, Dinglasan left to do missionary work with an international ministry, Couples for Christ, and was trained in the Philippines.

He worked in the poorest parts of the Philippines, and returned to the U.S. and did social justice work for the ministry in New Jersey and Chicago. He led youth retreats, created events, and ran social justice programs – building homes, entrepreneurship programs, schools, and clinics.

Music has also been part of Dinglasan’s ministry, he added, “I started filming myself singing songs for my team at the nonprofit because the pandemic was a dark time, to lift everybody’s spirits.”

It is important for him to connect with both his team and those who he is helping.

“Reaching out and being present in the community is going to be very much a part of what I do,” he said.